I adore creature comforts. Directed by Nick Park of Wallace and Grommet fame, it’s a british export brought to america to shed light on our thoughts on the most important issues of the day. In this example Donna sent over earlier today, a consideration on the topic of art. A delightful Friday diversion.

All posts by hugh

animal cruelty and the food supply

There are a lot of reasons to eat less meat, including personal health, the impact on climate change, and other environmental impacts, including pesticides and waste in rivers and waste in the water table.

And then there’s the issue of factory farms in general, and the question of how to assure that giant meat producers follow standards of quality and ethics. Large corporations, with a focus on the bottom line, place tremendous pressure on their employees to engage in unsafe and unethical practices. These bring out other concerns, including broader health concerns and the treatment of animals.

Today, the USDA announced the recall of 143 million pounds of beef produced by Westlake/Hallmark, based on the evidence presented in the following video, produced by an undercover reporter for the Humane Society of the United States. Before you watch it, you should know this video is one of the most disturbing things I’ve seen in a very long time.

In this facility, cattle who cannot stand on their own are lifted, rolled and speared by forklifts. Another has water shot into its nostrils to simulate drowning (cattle waterboarding, I suppose), and others are beaten in a routine and horrifying way. All in order to get sick cattle passed by the inspectors so they can be put into our food supply.

Unfortunately, most of the meat produced at this facility has already been eaten, and much of it (perhaps 37 million pounds) by children through school lunch programs. Two employees have been fired and charged with animal cruelty, but there are clearly deeply entrenched problems within this industry that aren’t addressed by punishing a couple of workers on the line. All in all, a deeply disturbing episode.

rethinking cultural heritage tourism

Promoting Heritage

I spent a couple of days last week attending the “Saving Places Conference” put on by the fine folks at Colorado Preservation. Colorado Preservation is recognized as one of the finest state organizations in the country focused on cultural heritage preservation. The Saving Places Conference is a great example of their excellent programs.

Part of the reason I was there was as a representative of The Friends of Historic Riverside Cemetery, as Riverside was selected as one of Colorado’s most endangered places for 2008.

But I was also interested in the theme of this year’s conference, “Promoting Colorado’s Heritage”; I wanted to find out whether there are some innovative approaches to creating compelling cultural heritage experiences for the broader community, not just for those who are dedicated preservationists (the more extreme of which are sometimes referred to as hysterical preservationists).

It was great to see so many people dedicated to preservation in one place; I’m not sure how many people were there, but it had to be about 300 or so, ranging from homeowners to architects to developers to representatives of the forest service. The sessions ranged from very detailed descriptions of how to engage in preservation activities (apparently there is no way to preserve a wooden grave marker) to the history of urban renewal (at some point, historic preservation became a key identity factor that brought investment into cities in a way that urban renewal couldn’t).

There was also a lot of focus on the relationship between green design and historical preservation – several of the presenters quoted Carl Elefante of Quinn Evans Architects as saying that “the greenest building is the one that’s already built.”

The connections between green design and historical preservation pointed to one of the implicit themes of the conference – the importance of making connections. Historical preservation doesn’t exist in a vacuum – it’s part of the fabric of our lives, adding richness and value without being a separate part of our experience. One of the keynote speakers at the conference, Daniel Jordan of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, said that preservationists are the “stewards of stories.” Yes, absolutely, but the stories of our lives are not one dimensional. We have to connect them to lived experience.

Why do you travel?

In general, people don’t like to be boxed in. History is boring, something you learn in school, heritage sounds boring, and culture sounds stuffy.

People travel for a wide variety of reasons, each tied to their own passions, to what they like to do. Some people like camping, hiking, and adventure. Some prefer the local beer, local food, or just hanging out with the locals.

And yet, when people travel travel, they regularly visit historic heritage and cultural sites. History adds the richness and texture to their travels. So, even though they don’t self-identify as historical travelers, in reality it’s an important part of the experience. In a sense, history, heritage, and culture are how we make the connection. It’s how we make the story make sense.

Making Connections

A couple of the presentations at the conference spoke to the importance of cross-pollinating heritage travel with other activities. For instance, on a panel on tourism in Southeastern Colorado a speaker mentioned the connection between natural and heritage travel – you can go birding on the plains (where you can see the lesser chicken and 400 other species of birds) while you are exploring the mountain branch of the Old Santa Fe Trail. Or, from a panel on ‘agri-tainment’ (now that’s a concept), Kelli Hepner talked about Delta County’s efforts to connect wine, orchards, the slow foods movement, and exploring the black canyon national monument.

All this is great, but what is difficult is communicating with individuals who don’t want to be boxed in based on my idea (or anyone’s idea) of what they should do. This is where I found people engaging in all sorts of clever technical tricks to find, rate, and ultimately decide on what to do when they travel.

There are some websites and applications that can help in this process. Yahoo Travel, Trip Advisor, Home and Abroad, and others attempt to bridge the gap between expert recommendations and personal preferences. To my mind, no one has done it in a truly effective way. It’s a challenging problem, but also a great opportunity. Ultimately, it could redefine the world of cultural heritage tourism.

The Old Cemetery is Dying

Riverside has been dying for a long time.

One of the first cemeteries in the american west designed as a park, with paths for carriages, and trees for shade, and roses, for a generation or so Riverside served as the resting place of the pillars of society, territorial governors and mayors and pioneers and publishers. It was filled with statuary and civil war heroes and abolitionists and shady characters and mothers who died in childbirth, and lots of children who died too young.

But it was downstream from the city, in an industrial area near the city of commerce, and it ended up on the wrong side of the tracks. Even before the Railway line came through, the wealthy had moved on to another part of town. Riverside was left to the working men and the working women, to immigrants and laborers and indigents.

And so there began a long, slow decline, the slow death of a place honoring the dead, exacerbated by the western thirst for water. It’s too far gone now, in many ways. Trees have died, and roses, and there will never again be kentucky blue grass between the graves. In the end, the old resting place will settle back into the dusty plains, as we’ll all settle into oblivion.

There is something profoundly human about the desire to immortalize ourselves with a mark in time. Perhaps it explains the creative impulse, the desire to say “I was here, now.” Or to commemorate a loved one with as generous a statement as you can afford.

In the early days of the american frontier, the cemetery was a primary form of expression, perhaps the only way for most people to say, I was here. I loved. I made my mark. And there is sadness in the realization that of all the monuments, each one for someone who lived and loved an died, so few stories survive.

There is an austere beauty to the prairie, and at Riverside it’s poignant given the location between the smelter and the refineries. It’s not a traditional beauty, not fecund and rich and fertile, but more elusive and fleeting and dry. Like the west, the prairie scene doesn’t give away it’s secrets. They are too valuable to waste on the unobservant.

Times change; the cemetery is no longer the tradition it once was. Burial is now the exception rather than the rule. Still, there’s something to looking to the past, something to gain from saving what’s left of this history.

For a while at least. Until oblivion.

Design Thinking in Higher Education

Overview

Over the past few years I’ve spent quite a bit of time working in the world of higher education, both as a consultant and an adjunct faculty member. It seems to me that the very institutions where students learn about the value of design thinking don’t internalize these ideas. Real opportunities for improved products and more effective communication are being missed.

This is not a situation that is unique to the educational system. In organizations that pay lip service to developing an innovative and entrepreneurial culture, the reality is that most have a long way to go to achieve the goal of encouraging real innovation among internal staff. Many organizations have hierarchical, decentralized, and consensus driven structures that lead to inefficiency based on “groupthinkâ€, lack of individual accountability, and a ‘keep your head down and it won’t get shot off’ mentality.

This is particularly true in the realm of higher education; with hundreds of years of tradition, institutions tend to be risk-averse and slow to change. But there is increasing pressure upon colleges and universities to become more responsive and entrepreneurial in their approach to problem solving, both in terms of curriculum and operations. From a curriculum perspective, some organizations have addressed this directly; for instance, Stanford has created the d.school, the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford, where they express their vision as follows:

We believe great innovators and leaders need to be great design thinkers.

The Stanford ‘design manifesto’ goes on to say the following:

We believe having designers in the mix is key to success in multidisciplinary collaboration and critical to uncovering unexplored areas of innovation. Designers provide a methodology that all parties can embrace and a design environment conducive to innovation. In our experience, design thinking is the glue that holds these kinds of communities together and makes them successful.

Stanford is not alone in embracing the value of design thinking; for instance, in a recent article in Business Week Online (“Bob Kerrey Gets Innovation Right At The New School And Parsonsâ€, published March 18, 2007) Bruce Nussbaum says:

Design thinking is seen as the integrative solvent that brings together the programs through a powerful methodology that solves a myriad of problems. […] Kerrey, in particular, was right on. He is leading a major move to make The New School more innovative and to teach innovation throughout its programs.

Kerrey wants to implement design thinking not just within the curriculum but also throughout the institution. Opportunities for real innovation are available to those institutions that engage in design thinking; but most will have to work through some fairly substantial issues before they can take advantage of it. Designers, writers, and other creative team members working in these institutions should become the advocates for real change.

Internal Agency, Strategic Partner

Design teams are in a complicated position within universities; they not in a position to refuse projects, and even in a changing environment are still responsible for achieving revenue goals. The ability of design departments to advocate for new approaches is dampened by the need to constantly crank out large numbers of projects without having the opportunity to pick and choose.

Because of their historical role and the inherent complexities of running an internal design department, internal teams don’t get the respect that outside consultants receive (it’s an offshoot of the ‘you can’t get respect in your home town’ mentality).

This reality is not caused by lack of professionalism on the part of the internal team. In fact, to some extent the desire to placate a client, to ‘give them what they want’, can cause strains on relationships and the delivery of products that are less than satisfactory. In order to improve the standing of the group within the University, a new and less democratic (though no less professional) approach to project definition needs to be employed.

Step 1: Differentiate Between Projects

Internal agencies may not be able to refuse work from within their institution, but it is still important to identify the nature of the project and apply the appropriate resources to assure a successful completion. One way to differentiate between projects is to place them within a simple grid, where one axis identifies the value of the project (from ‘production’ to ‘strategic’), and the other outlines the timeline (from ‘normal’ to ‘urgent’).

Whenever possible, internal resources should be working on projects with strategic importance and normal timelines, as these projects generally provide the most value for the organization while increasing the resident intellectual capital. These types of projects also improve the morale of the team, as they are more interesting and less stressful than urgent production projects. The goal is to move toward engaging in more strategic projects, and then to apply the principles of design thinking to those projects.

Step 2: Apply “Design Thinking†to Strategic Projects

1. Employ User-Centered Design

Techniques such as Observation, Research, Personas, and Scenarios help to establish a shared understanding of the project vision and encourage both the clients and the design team to look at the design problem from a different perspective.

2. Collaborate Aggressively

While it is tempting to set up a perimeter around the internal team and ‘man the barricades’, this may in fact be counterproductive. Hierarchical approaches do not lend themselves to effective collaboration. It is more effective to offer a willingness to engage with projects that are strategic in nature without preconceptions, but with confidence that designers have an essential role to play in building the University of the future.

3. Prototype Relentlessly

Industrial Designer Ashe Birsal had a professor at Pratt who told her to “Mock it up before you fock it up.†Tim Brown of Ideo calls it the “Build to Think†mentality. In his book ‘Serious Play’, Michael Shrage calls it ‘Externalized Thought,’ and goes on to say:

“Mental models become tangible and actionable only in the prototypes that management champions… Models are not just tools for individual thought. They are inherently social media and mechanisms.â€

Prototypes allow us to share our ideas in a concrete manner.

4. Tell Stories

Stories are how people connect. Strategic projects require narratives. Effective teams us multi-disciplinary, scenario-based stories that engage the client and disarm the arguments.

User-Centered approaches, collaborative teams, prototypes, and narrative combine to create a design approach that can allow internal design teams to change the nature of the game. By employing Design Thinking, you have the opportunity to invent the future.

Resources:

yes we can

Will.i.am of the black eyed peas produced this music video with the help of numerous musicians and hollywood types. The celebrity component is a bit superfluous (I’m not sure what Scarlett Johanssen is doing in there), but all in all it’s pretty compelling.

Tomorrow, I will be caucusing for Barack Obama.

The end of consumer culture?

Should designers work toward the end of aspirational consumer culture? Can the design industry, broadly defined, reposition and reinvent itself to provide value and sustainability while still creating desire?

When I was at Northwestern, I took some classes from a Professor of Philosophy, David Michael Levin, who once asked us whether having a choice was important in our lives. Specifically, he was asking about the difference between choice and the appearance of choice. For instance, he asked, is it important to be able to choose between Crest and Colgate?

I think of Professor Levin from time to time, and often when I’m walking down the personal care aisle of the supermarket. Looking at all the variations of toothpaste and related products (Whitestrips, anyone?), I wonder whether it’s possible that our society in general may have gone just a bit too far, and that the designers and product managers and marketers are spending too much of their creative resources on selling products with limited value and without any real differentiation.

I’m not arguing that there isn’t valuable product innovation going on, but I tend to doubt the big change involves one of the 50 swirly paste/gel combos on every American supermarket aisle. Think of the improved efficiencies we’ll see just as soon as all the rest of you realize that Tom’s of Maine Peppermint is plenty good enough for everyone.

Innovation, or Variation?

Okay, that’s probably not going to be happening any time soon. And, if there were only one kind of toothpaste, I’d likely never gotten the chance to try out Tom’s products, or the cool toothpaste that combines gel, paste, and some crazy sparkly bits. I do love the crazy sparkly bits.

I’m not recommending some sort of centralized control of the means of production; it wouldn’t work anyhow, not in the fast moving consumer goods market, and certainly not in the broader markets. But there’s still something decadent and even unethical about the way we sell the aspirational in consumer goods.

Of course, if people didn’t want it, we wouldn’t sell it, and the invisible hand of the market will ultimately level everything out, right? Well, maybe.

The toothpaste reference is pretty trivial, but it points to a bigger question about designer culture. Designer culture is still about the aspirational, and it’s well established in mainstream markets.

Rob Horning wrote an article on Pop Matters called The Design Imperative. In it, he considers both the historical underpinnings and the current nature of our consumer culture. Historically,

the consumer revolution depended on the sudden availability of things, which allowed ordinary people to buy ready-made objects that once were inherited or self-produced.

and in our current world,

We are consigned to communicating through design, but it’s an impoverished language that can only say one thing: “That’s cool.” Design ceases to serve our needs, and the superficial qualities of useful things end up cannibalizing their functionality.

The problem ultimately is that all this consumption fills some sort of void in our lives, at least temporarily. And by feeding the void in our lives, designers are providing the stimulus that keeps the modern economy moving.

It’s the economy, stupid

According to the news reports I’ve been reading, the economy of the United States has a pretty good chance of heading into a recession for most if not all of 2008. One of the primary causes, resulting in part from the rocking of the financial markets due to sub-prime lending, is decreased consumer spending. Consumer spending, which accounts for two thirds of economic activity, weakened in the month of December.

But for those of us who would like to see a decrease in consumption, is this necessarily bad news?

After the terrorist attacks in 2001, I remember being slightly horrified by Bush the 43rd admonishing the people of America to ‘go shopping’ to fight back against terrorism. Of course, there was an important idea in there somewhere, that we shouldn’t allow our lives to be controlled by a few fundamentalist wackos. But I found it hard to believe that a trip to wal-mart was the best way to fight back against Osama bin Laden. It’s a long way from the Victory Gardens our grandparents planted to help win World War II.

I was thinking about this when I came across an excellent article by Madeleine Bunting, published in the Guardian, called “Eat, drink and be miserable: the true cost of our addiction to shopping”.

As Ms. Bunting points out:

We have a political system built on economic growth as measured by gross domestic product, and that is driven by ever-rising consumer spending. Economic growth is needed to service public debt and pay for the welfare state. If people stopped shopping, the economy would ultimately collapse. No wonder, then, that one of the politicians’ tasks after a terrorist outrage is to reassure the public and urge them to keep shopping (as both George Bush and Ken Livingstone did). Advertising and marketing, huge sectors of the economy, are entirely devoted to ensuring that we keep shopping and that our children follow in our footsteps.

The question that I have been wrestling with regarding this question is how we can both decrease our rampant disposable consumerism while still continuing to have a reasonably robust economy. How am I supposed to continue pushing the economy forward while cutting my carbon footprint by 60 percent?

Happy Now?

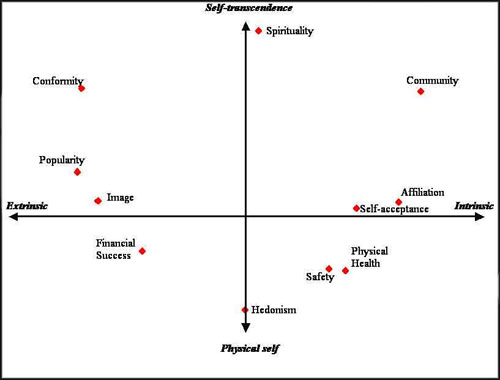

In her article, Ms. Bunting discusses the work of Tim Kasser, an American Psychologist concerned with materialism, values, and goals. Kasser has created an aspirational index which helps to distinguish between two types of goals:

Extrinsic, materialistic goals (e.g., financial success, image, popularity) are those focused on attaining rewards and praise, and are usually means to some other end. Intrinsic goals (e.g., personal growth, affiliation, community feeling) are, in contrast, more focused on pursuits that are supportive of intrinsic need satisfaction.

According to Kasser, he would like to “help individuals and society move away from materialism & consumerism and towards more intrinsically satisfying pursuits that promote personal well-being, social justice, and ecological sustainability.”

Personally, I’m not quite sure where I fall on the Aspirational Index.

I try to be mindful of what I’m consuming, where it comes from, and where it ends up. Still, I have a couple pair of shoes that I bought on a whim, and a jacket I didn’t wear more than a few times. I don’t get a whole lot of joy out of going shopping, whether for clothes or anything else, but I’m sure there are many, many ways I could do more with less.

It occurs to me that there needs to be a new paradigm of consumption, one that will work for business, community, and environment. I don’t know what form this new paradigm will take, but I believe it has something to do with learning to appreciate the real value of things and their place in our world.

Designers have an opportunity to engage in this paradigm shift. Part of the story lies in creating products that have intrinsic and lasting value, products that I like to call artisanal. And part of the story lies in better communicating the value of the artisanal. I believe that designers have an ethical duty to work toward the end of disposable culture. Of course, this isn’t going to happen overnight, and it’s not going to happen in vacuum. But it is going to happen, whether we choose to be a part of the process or not. Better to engage the future rather than have it thrust upon us.

Toward a Moral Equivalent of Consumerism

The subtitle of Madeleine Bunting’s Guardian article is “Today it seems politically unpalatable, but soon the state will have to turn to rationing to halt hyper-frantic consumerism”. She speaks to the inevitability of changing our behaviors, and believes that the change will not happen without intervention from the state. Whether it is rationing, or taxes, or other means, the change, ultimately, will have to come.

But change is never easy or simple. In The Moral Equivalent of War (1906), William James explained the difficulties of advocating pacifism:

So far, war has been the only force that can discipline a whole community, and until an equivalent discipline is organized, I believe that war must have its way.

War, like consumer capitalism, offers a way of getting people motivated and organized. Adam Smith, in “The Wealth of Nations”, argues that “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self interest.” Self interest is a strong motivational force, and unless and until there is a “Moral Equivalent of Consumerism” it may well be impossible to create an alternative solution.

It will likely be necessary for government to engage in rationing or taxation to decrease our impact on the environment. But there is also an important component that should not be ignored, and one that can and should be engaged in by the designers of our products and communications. A new aspiration, perhaps focused on the intrinsic and self-transcendent as Tim Kasser explains. A aspiration toward what is valuable, an experience where less is truly more.

In “The Moral Equivalent of War”, James argues that:

Great indeed is Fear; but it is not, as our military enthusiasts believe and try to make us believe, the only stimulus known for awakening the higher ranges of men’s spiritual energy.

In seeking a moral equivalent of consumerism it is our challenge to use our capabilities to awaken the higher ranges of each person’s spiritual energy, and to produce objects and communications that are filled with value.

Should designers work toward the end of aspirational consumer culture? Ultimately, I’m not sure there is any other choice.

The Designers Accord

I joined the Designers Accord this past week.

What is the Designers Accord? According to founder Valerie Casey, it “is a call to arms for the creative community to reduce the negative environmental and social effect caused by design.”

I think of it as a more modern version of the hippocratic oath for designers. It’s not just a call to arms, it’s a code of ethics, a responsibility to think through every decision you make as a designer with as much perspective as you can muster.

In fact, the first tenet of the code of conduct expressed on the site is “do no harm”. This term, derived from a core tenet of medical practice (though not, in fact, from the hippocratic oath – the term Primum non nocere has been used for the past 150 years) is essentially conservative in nature. Don’t do anything to make the situation worse. A good start, though not going far enough. The code of conduct continues:

Do no harm

Communicate and collaborate

Keep learning, keep teaching

Instigate meaningful change

Make theory action

The Designers Accord focuses primarily on environmental components, though I believe that there are social justice components implicit in the initiative as well. And it is not just designers who should consider these issues – though designers have been responsible for making more than their fair share of trash in the past. But this is a consideration for all of us in our daily lives.

In her (newly reinitiated) column on design in the New York Times yesterday, Allison Arieff says that the Designers Accord is going to be endorsed by both the American Institution of Graphic Arts (AIGA) and Industrial Design Society of America (IDSA). She also says:

Recognizing the near impossibility of changing consumer behavior and business behavior alike, the Designers Accord asserts that these firms, which design everything from graphics and packaging to user interface to final product, are ideally suited to get the design-for-impact conversation rolling.

In some ways these are heady times for designers. Rock star architects and product designers for Target and the latest electronic gizmo. But there has to be a way to creatively engage each client, each individual, in a conversation that pushes all of us to provide more value with less impact.

Kudos to Valerie Casey for starting this initiative. Now, let’s get to work.

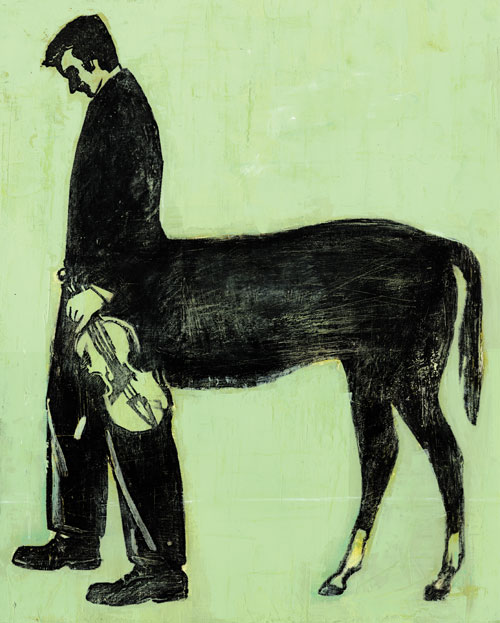

STORY: at the metro center for visual arts

Hadley, along with Brent Green and James Surls, is exhibiting in the current show at the Metro State Center for Visual Art. Entitled “Story”, the exhibition “brings together three artists whose artwork has a tale to tell. The exhibition is a profound collection of works that delve into created realities and visually realized narratives of the strange and familiar.”

When I met hadley, 19 years ago or so, I was immediately struck by the incredible layers of meaning in her paintings and sculpture. I remember commenting that nothing in her work is what it seems on the surface. It’s not surprising I suppose, given my interest in stories, that I fell in love with a woman who is a better storyteller than I am. I’m sure the understanding of narrative is part of why hadley is such a successful illustrator, but her paintings are another level of expression, and really where she puts her heart.

Narrative in the visual arts has come back into style since the heyday of the abstract expressionists.Today, I don’t think many people would stand behind this quote from Clive Bell, which he wrote in support of the abstract expressionists non-objective paintings:

The representative element in a work of art may or may not be harmful, but it is always irrelevant. For to appreciate a work of art, we must bring with us nothing from life, no knowledge of its affairs and ideas, no familiarity with its emotions.

Like a good pop song, the best narrative paintings tell open-ended stories. As Mary Chandler wrote in her review of the show in the Rocky Mountain News, Hadley’s work consists of “lushly textured paintings – paint, ink and toner on Venetian plaster – that follow one of the big rules of art: that work should ask as many questions as it answers”

Kudos to the team at the CVA, who have paired hadley with Brent Green, who creates brilliant animations (as well as working with musicians like Califone and Giant Sand and Fugazi among others), and James Surls, who builds fascinating hanging sculpture; the show holds together really well.

The show opens with a public reception on Thursday, January 10th from 7 to 9pm. More information is available on the CVA website.

“what if?” design

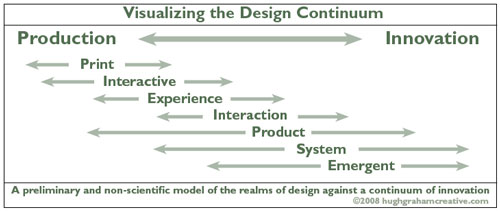

The Design Continuum

Design rests on a continuum between production and innovation. Along this continuum, whether working in product, communication, or interaction, designers focus on providing a compelling experience, an experience that is useful, usable, and desirable (or, as the architect Vitruvius wrote in the first century BCE, firmitas, utilitas, venustas).

In those realms of design that are mature as a practice, it’s not necessary to invent new approaches in order to provide their audience with a satisfactory experience. For instance, print design for corporate reports or brochures or magazines may benefit from new approaches, but in a narrow sense innovation isn’t required to be successful. These design realms lie closer to the production end of the spectrum.

While there are many designers doing successful work in these fields who don’t feel the need to change the recipe for success, others are feeling “the squeeze of print” during our time of interactivity and connectedness and environmental awareness. Many writers, illustrators, and graphic designers have taken the best practices of print communications and are now applying them to the web and interactive world. For these artists, it’s not too great a stretch to design for interactivity.

These artists are well-served by understanding basic principles of people-centered research and design, but a deep knowledge of these realms isn’t absolutely necessary for their work to be successful and engaging and compelling. The intersection of motion design principles with ‘swiss’ design grids and hierarchies is bringing out some great design work. But most of the change is formal rather than essential.

Designing Change

For many designers, interactivity and connectedness and socially responsible approaches have led to new paradigms; there is an increasing overlap between the worlds of ‘strategy’ and ‘design’. Business strategy in particular is closely aligned to design innovation; in fact, it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference between the two, though there are important differences. What are the specific approaches that allow designers to create new products? And how do these approaches align and diverge?

As we look at the new paradigms in contemporary design practice, there are many terms currently in play. For instance, design thinking has gotten a lot of press, and there are other terms bandied about to describe these new approaches; people-centered design, participatory design, interaction design, metadesign, concept design, systems design, innovation design, and story-centered design are just a few, and each speaks to some part of this evolving approach to designing change.

It’s possible to consider all of these as components of a broader world of design strategy. At the least, they tend to share some characteristics; for instance, most combine research and generative components, advocate for iterative methods, and encourage the use of narrative as a tool for discovery.

Research Components

The value of ethnographic and other qualitative research techniques in the development of people centered design is broadly understood and accepted. Observation, interviews, journaling, and other techniques offer designers working in a variety of fields (product, experience, communications, interaction, etc.) the opportunity to gain insights that inform the design process.

Some research approaches are comprehensive and take a considerable amount of time and expense to complete, while others focus on quicker turnaround with a guerilla attitude. The appropriate combination of research components has to be tailored for each design problem, and may vary from conducting a few interviews with friends to spending months or even years recording the behaviors of whole families or organizations.

What is undeniable is the value of conducting some research on any innovation project; you don’t want to overbuild your initial solution, but a key component of designing innovation is “getting out of your head†and understanding the perspective of the person who will be using your product. Even short research can often reveal adaptive and compensatory behaviors as well as individual peculiarities that help to inform the design process.

For instance, I conducted a series of interviews with University of Denver students recently, and found both surprising alignment and extensive differences both in terms of behavior and values. A well-conducted interview can reveal quite a bit, but I’ve also had great success using participant photo journals to explore beyond the time limitations of the interview session. More extensive research programs have been used to create whole new product categories.

Rick Robinson, formerly of eLab and Sapient, and now at Continuum, has defined an ethnography as follows:

- A description, of a system, activity, belief, setting, culture, etc.

- and interpretation – not just a summary-of that description

- toward an end – both instrumental and salient

- within constraints – of site, setting, time, tools, materials, and solution spaces

Whatever the scope of the research project, understanding the importance of interpretation, goals, and limitations is critical to success. This is not research for research sake; the findings may be surprising, but the goals should be well-defined.

Generative Components

I have written extensively on story-centered design; it’s an effective approach to collaborative problem solving, particularly as a tool to help generate new ideas. This approach is gaining broader interest and acceptance, especially among interaction and product designers. In an article titled “Creative gesture or vapid prototyping? The importance of fictional products” posted on the adobe design center site, Allan Chochinov of Core 77 says the following:

Too many of our products are function first/form second—or form first/function second—with narrative, story-telling elements nowhere to be found. How bad would it be if our products began with narrative in the first place; with an idea of the experience of the product in mind, before that product ever had the chance to turn into landfill? Not bad at all, really.

He goes on to quote Scott Klinker of Cranbrook who argues that:

more and more product designers are now exploiting the power of storytelling to probe user behaviors, find experience “touchpoints,” create novel forms, and ultimately deliver new product experiences.

As with research techniques, narrative exploration needs to be focused on well-defined goals; stories need to be individualized and involve specific interactions. Story-centered design is a method that needs to be combined with other design approaches to be used successfully.

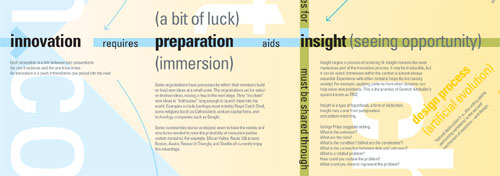

Innovation Design, understood broadly, provides a rubric that can help to understand the components involved in the process. In the current issue of Interactions Magazine (published by the Association for Computing Machinery), Hugh Dubberly offers A Model of Innovation that explores a lot of these parameters. The introduction to the article states:

As businesses have become good at managing quality, quality has become a sort of commodity – “table stakes,†necessary but not sufficient to ensure success. When everyone offers quality, quality no longer stands out. Businesses must look elsewhere for differentiation. The next arena for competition has become innovation. The question becomes: Can innovation be “tamed†as quality was?

One component that Dubberly discusses in his model is the importance of values (beliefs may lead to actions may lead to artifacts). Experience shows that an iterative design process based in the experience of the individual requires grounding in the importance of providing value.

Emergent Design

There is a facet of the design process that isn’t satisfactorily described by any of these terms; specifically, the experience of design as iterative, evolutionary, and, in a sense, out of the designers control. I’ve written about this before when discussing the work of Jan Chipchase, who argues that designers provide the basic functionality, and the extensions are added by the users. How do we design for a future that we can’t foresee? The best term I’ve heard for this is ’emergent design’.

I first started considering the idea of emergent design based on reading Henry Jenkins ideas of “emergent narratives” in his description of Game Design as Narrative Architecture:

in the case of emergent narratives, game spaces are designed to be rich with narrative potential, enabling the story-constructing activity of players. In each case, it makes sense to think of game designers less as storytellers than as narrative architects.

If we abstract the idea of emergent narratives beyond games, perhaps emergent design offers the opportunity to describe a design process that is equally “rich with narrative potential” while inclusive of other design methods (for instance, ethnographic research and prototyping). It points to iterative and participatory approaches, without requiring a particular methodology.

In an article titled “Emergent Design and learning environments: Building on indigenous knowledge” published the IBM Systems Journal (Volume 39, Numbers 3 & 4, 2000), David Cavallo of the MIT Media Laboratory says this of the limitations of current approaches to systems design:

When the desired changes cannot be reliably foreseen, and particularly when the target domain is computationally too complex for automation and thus relies on the understanding and development of the people involved, then top-down, preplanned approaches have intrinsic shortcomings and an emergent approach is required.

[…]

The critical point is that adoption and implementation of new methodologies needs to be based in, and grow from, the existing culture, and typically fails when it is merely imposed from above without such cultural considerations.

What If?

Going back to Allan Chochinov’s discussion of ‘fictional design’, we find a great summary of the emerging approach to designing for change:

Playing out “what if” scenarios has well served designers, conceptual artists, and provocateurs of all stripes to explore their craft; to take license (or to take “design permission,” using Leonard’s phrase) with what is expected, what is sensible, or what is pragmatic. Design fictions remake the playing field into something beyond a commercial go/no go enterprise; they let designers ask “what if?”

Of course, there always has to be balance between production and innovation. But more and more there is a need to ask what if, to get out of our own heads, to explore, to innovate our way into the future.