Should designers work toward the end of aspirational consumer culture? Can the design industry, broadly defined, reposition and reinvent itself to provide value and sustainability while still creating desire?

When I was at Northwestern, I took some classes from a Professor of Philosophy, David Michael Levin, who once asked us whether having a choice was important in our lives. Specifically, he was asking about the difference between choice and the appearance of choice. For instance, he asked, is it important to be able to choose between Crest and Colgate?

I think of Professor Levin from time to time, and often when I’m walking down the personal care aisle of the supermarket. Looking at all the variations of toothpaste and related products (Whitestrips, anyone?), I wonder whether it’s possible that our society in general may have gone just a bit too far, and that the designers and product managers and marketers are spending too much of their creative resources on selling products with limited value and without any real differentiation.

I’m not arguing that there isn’t valuable product innovation going on, but I tend to doubt the big change involves one of the 50 swirly paste/gel combos on every American supermarket aisle. Think of the improved efficiencies we’ll see just as soon as all the rest of you realize that Tom’s of Maine Peppermint is plenty good enough for everyone.

Innovation, or Variation?

Okay, that’s probably not going to be happening any time soon. And, if there were only one kind of toothpaste, I’d likely never gotten the chance to try out Tom’s products, or the cool toothpaste that combines gel, paste, and some crazy sparkly bits. I do love the crazy sparkly bits.

I’m not recommending some sort of centralized control of the means of production; it wouldn’t work anyhow, not in the fast moving consumer goods market, and certainly not in the broader markets. But there’s still something decadent and even unethical about the way we sell the aspirational in consumer goods.

Of course, if people didn’t want it, we wouldn’t sell it, and the invisible hand of the market will ultimately level everything out, right? Well, maybe.

The toothpaste reference is pretty trivial, but it points to a bigger question about designer culture. Designer culture is still about the aspirational, and it’s well established in mainstream markets.

Rob Horning wrote an article on Pop Matters called The Design Imperative. In it, he considers both the historical underpinnings and the current nature of our consumer culture. Historically,

the consumer revolution depended on the sudden availability of things, which allowed ordinary people to buy ready-made objects that once were inherited or self-produced.

and in our current world,

We are consigned to communicating through design, but it’s an impoverished language that can only say one thing: “That’s cool.” Design ceases to serve our needs, and the superficial qualities of useful things end up cannibalizing their functionality.

The problem ultimately is that all this consumption fills some sort of void in our lives, at least temporarily. And by feeding the void in our lives, designers are providing the stimulus that keeps the modern economy moving.

It’s the economy, stupid

According to the news reports I’ve been reading, the economy of the United States has a pretty good chance of heading into a recession for most if not all of 2008. One of the primary causes, resulting in part from the rocking of the financial markets due to sub-prime lending, is decreased consumer spending. Consumer spending, which accounts for two thirds of economic activity, weakened in the month of December.

But for those of us who would like to see a decrease in consumption, is this necessarily bad news?

After the terrorist attacks in 2001, I remember being slightly horrified by Bush the 43rd admonishing the people of America to ‘go shopping’ to fight back against terrorism. Of course, there was an important idea in there somewhere, that we shouldn’t allow our lives to be controlled by a few fundamentalist wackos. But I found it hard to believe that a trip to wal-mart was the best way to fight back against Osama bin Laden. It’s a long way from the Victory Gardens our grandparents planted to help win World War II.

I was thinking about this when I came across an excellent article by Madeleine Bunting, published in the Guardian, called “Eat, drink and be miserable: the true cost of our addiction to shopping”.

As Ms. Bunting points out:

We have a political system built on economic growth as measured by gross domestic product, and that is driven by ever-rising consumer spending. Economic growth is needed to service public debt and pay for the welfare state. If people stopped shopping, the economy would ultimately collapse. No wonder, then, that one of the politicians’ tasks after a terrorist outrage is to reassure the public and urge them to keep shopping (as both George Bush and Ken Livingstone did). Advertising and marketing, huge sectors of the economy, are entirely devoted to ensuring that we keep shopping and that our children follow in our footsteps.

The question that I have been wrestling with regarding this question is how we can both decrease our rampant disposable consumerism while still continuing to have a reasonably robust economy. How am I supposed to continue pushing the economy forward while cutting my carbon footprint by 60 percent?

Happy Now?

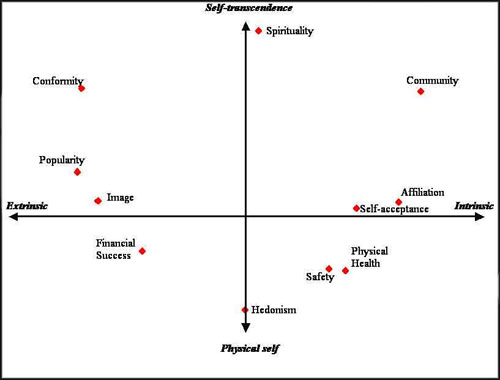

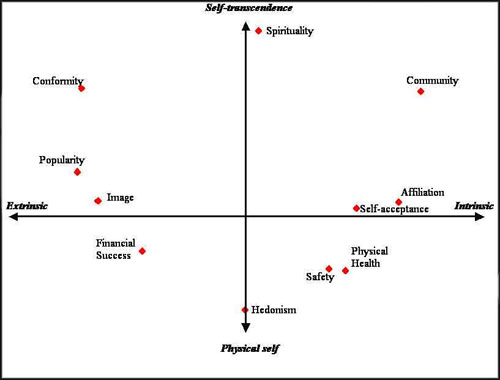

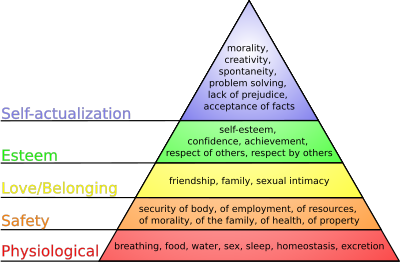

In her article, Ms. Bunting discusses the work of Tim Kasser, an American Psychologist concerned with materialism, values, and goals. Kasser has created an aspirational index which helps to distinguish between two types of goals:

Extrinsic, materialistic goals (e.g., financial success, image, popularity) are those focused on attaining rewards and praise, and are usually means to some other end. Intrinsic goals (e.g., personal growth, affiliation, community feeling) are, in contrast, more focused on pursuits that are supportive of intrinsic need satisfaction.

According to Kasser, he would like to “help individuals and society move away from materialism & consumerism and towards more intrinsically satisfying pursuits that promote personal well-being, social justice, and ecological sustainability.”

Personally, I’m not quite sure where I fall on the Aspirational Index.

I try to be mindful of what I’m consuming, where it comes from, and where it ends up. Still, I have a couple pair of shoes that I bought on a whim, and a jacket I didn’t wear more than a few times. I don’t get a whole lot of joy out of going shopping, whether for clothes or anything else, but I’m sure there are many, many ways I could do more with less.

It occurs to me that there needs to be a new paradigm of consumption, one that will work for business, community, and environment. I don’t know what form this new paradigm will take, but I believe it has something to do with learning to appreciate the real value of things and their place in our world.

Designers have an opportunity to engage in this paradigm shift. Part of the story lies in creating products that have intrinsic and lasting value, products that I like to call artisanal. And part of the story lies in better communicating the value of the artisanal. I believe that designers have an ethical duty to work toward the end of disposable culture. Of course, this isn’t going to happen overnight, and it’s not going to happen in vacuum. But it is going to happen, whether we choose to be a part of the process or not. Better to engage the future rather than have it thrust upon us.

Toward a Moral Equivalent of Consumerism

The subtitle of Madeleine Bunting’s Guardian article is “Today it seems politically unpalatable, but soon the state will have to turn to rationing to halt hyper-frantic consumerism”. She speaks to the inevitability of changing our behaviors, and believes that the change will not happen without intervention from the state. Whether it is rationing, or taxes, or other means, the change, ultimately, will have to come.

But change is never easy or simple. In The Moral Equivalent of War (1906), William James explained the difficulties of advocating pacifism:

So far, war has been the only force that can discipline a whole community, and until an equivalent discipline is organized, I believe that war must have its way.

War, like consumer capitalism, offers a way of getting people motivated and organized. Adam Smith, in “The Wealth of Nations”, argues that “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self interest.” Self interest is a strong motivational force, and unless and until there is a “Moral Equivalent of Consumerism” it may well be impossible to create an alternative solution.

It will likely be necessary for government to engage in rationing or taxation to decrease our impact on the environment. But there is also an important component that should not be ignored, and one that can and should be engaged in by the designers of our products and communications. A new aspiration, perhaps focused on the intrinsic and self-transcendent as Tim Kasser explains. A aspiration toward what is valuable, an experience where less is truly more.

In “The Moral Equivalent of War”, James argues that:

Great indeed is Fear; but it is not, as our military enthusiasts believe and try to make us believe, the only stimulus known for awakening the higher ranges of men’s spiritual energy.

In seeking a moral equivalent of consumerism it is our challenge to use our capabilities to awaken the higher ranges of each person’s spiritual energy, and to produce objects and communications that are filled with value.

Should designers work toward the end of aspirational consumer culture? Ultimately, I’m not sure there is any other choice.

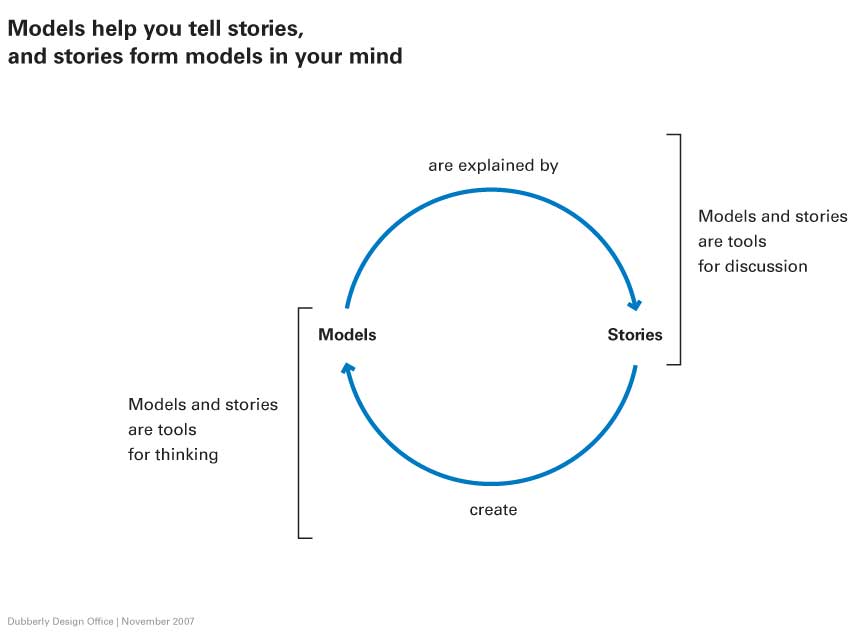

Stories are how people communicate; this is as true in design and business as in our personal lives. From developing the initial vision for a project through implementing the solution, any complex project requires consideration of numerous points of view. Ultimately, the best solution is the one that most elegantly and simply addresses the needs and desires of the various audiences, and narrative approaches provide an effective tool in helping to define, share, and develop that solution.

Stories are how people communicate; this is as true in design and business as in our personal lives. From developing the initial vision for a project through implementing the solution, any complex project requires consideration of numerous points of view. Ultimately, the best solution is the one that most elegantly and simply addresses the needs and desires of the various audiences, and narrative approaches provide an effective tool in helping to define, share, and develop that solution.

Similarly, mobile email wasn’t something that the students used on a regular basis. Unlike business users (like myself), with our addiction to our ‘crackberries’, the immediate access to email isn’t that important to students. They are okay with accessing their email via their laptop, and if they don’t get an email message immediately it’s not a cause for concern. Usually they check their email (often through a web browser) as they’re getting into their work process. Check email, check a couple of news sites, and then settle in to do your homework.

Similarly, mobile email wasn’t something that the students used on a regular basis. Unlike business users (like myself), with our addiction to our ‘crackberries’, the immediate access to email isn’t that important to students. They are okay with accessing their email via their laptop, and if they don’t get an email message immediately it’s not a cause for concern. Usually they check their email (often through a web browser) as they’re getting into their work process. Check email, check a couple of news sites, and then settle in to do your homework.