note: these thoughts are based on a presentation I made this past friday at the Image Space Object conference.

I’m interested in new forms of storytelling, and especially the use of storytelling in designing innovative products and services. I’m also interested in historical forms and variations of stories, and their value for people’s lives.

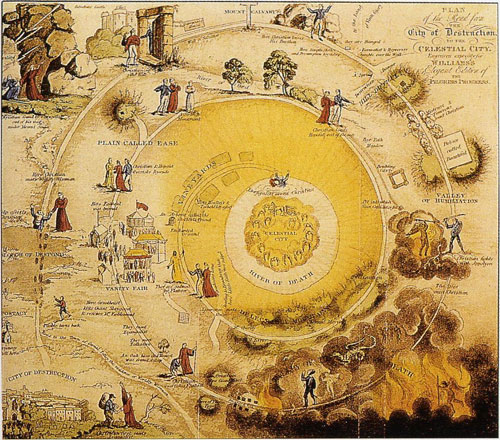

I love the story of the Pilgrim’s Progress, if only because it helps put our own lives in context. However complex and difficult our lives may be, and with all the challenges we face, it seems unlikely that our lives are more difficult than that of the medieval everyman.

If, as William Blake said in Proverbs of Hell, “Improvement makes straight roads; but the crooked roads without improvement are roads of Genius,†then our goal is to walk down the winding path without knowing all its twists and turns.

My own background is in performance and storytelling; I started working in interactive media in the early nineties. The addition of interactivity caused me to rethink the nature of telling stories; over time I came to believe that personal stories are the most vital and compelling, but as I began to consider interactivity I was thrown into a world where there was no longer control the way the story is experienced; how do we communicate themes and messages if there is no plot, no defined beginning, middle, and end?

One way to frame this new form of storytelling is to think of it as a conversation between the author and the audience; by its nature a conversation has a spontaneous and uncontrolled feel, and yet it can also be structured and composed. Conversations wander crooked roads, but they are informed by the needs and desires of the participants.

There is a natural tendency among creative people to believe that great work leaps fully formed into the world like Athena from the head of Zeus, but when we are creating complex projects that require interaction both between various team members and audiences, this is a risky proposition to say the least. This is another reason I prefer to frame the design process as a creative dialogue. In a dialogue we don’t know where the conversation will take us; the uncertainty of the end-result is part of the creative process.

The Design Imperative

The quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning. Uncertainty is the very condition to impel man to unfold his powers. Creativity requires the courage to let go of certainties.

~ Erich Fromm

Change is always tough. Facing the uncertain, considering the void, going to the dentist. And certainly our experience is that the pace of change is increasing. It’s not clear whether the stress of change on a personal level is greater than at times in the past, but clearly we are more directly connected to one another globally.

With climate change, globalization, social and political upheaval, and technological acceleration, the risk is that the gap will be filled with alienation, hopelessness, and reactionary nostalgia. The fact of the matter is that in the future we will all have to make due with less stuff. The potential for a bleak future is very real; the goal of voluntarily decreasing consumption and reducing our environmental impact can only be achieved if we are offered a corresponding richness of experience.

We will eventually have to engage in a revaluation of all values (as Nietzsche referred to it), and it will not be an easy sell. Changing consumer behavior will require real design innovation (as well as changes in our behavior as designers) from throughout the design disciplines. Through creativity, imagination, and innovation we have the opportunity and responsibility to model the future, to create the world that we will live in.

This all sounds very bleak and serious, but ultimately the imperative is to find opportunities for joy, humor and fun in our products, processes, and interactions. Not superficial pleasure based in the avoidance of the real, nor a “whistling past the graveyard†gallows humor, but authentic pleasure based in creativity and personal growth. And not just for us as designers, but also for our audience.

Our task is to engage our audience in an ongoing, iterative, and authentic dialogue. But let’s not take ourselves too seriously, or we risk missing out on the pleasure of honest work. To be true to ourselves, to be authentic, we should look around corners and find the unexpected surprises and delights that await us there.

The Search for Authenticity

“No authentic human life is possible without irony”

Soren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Irony (1840)

Lately, the term authenticity seems to be resurfacing in the lexicon of the business community. There’s a new book on the topic, and I’ve encountered it in some of the research and design work I’ve done with my clients. Its use can be problematic, and there is a tendency to be either too flip in throwing it around, or alternately dismissive of the value of its consideration.

When I was in college I read a lot of existential philosophy, and authenticity is a prominent term of study in that area.

By the way, I’m a strong believer in what Steve Martin once said: “If you’re studying geology, which is all facts, as soon as you get out of school you forget it all, but with philosophy you remember just enough to screw you up for the rest of your life.†So, if you are wise you won’t assume that my memories of philosophy are based in any reality.

But nonetheless, my understanding is that authenticity is closely aligned with courage and honesty in the face of outside forces; the authentic individual is one who does what is true and right and ethical despite the pressures put on us by society. It’s a simple idea, but one that is very difficult to put into practice; there are always competing exigencies in our work and lives, and the lines are not always clearly drawn. But the risks are also high, given the importance of the choices we make in our daily lives.

“We have a hunger for something like authenticity, but are easily satisfied by an ersatz facsimile.” -George Orwell, c. 1949

I was recently sent an invitation to attend a conference conducted by James Gilmore and Joe Pine, who wrote ‘The Experience Economy’ several years ago. As part of the invitation they sent out the first chapter of their new book called “Authenticity: What Consumers Really Wantâ€. The conference is called ‘ThinkAbout’ and it’s taking place this year in Nashville. The logo is a great facsimile of letterpress printing, and is definitely an example of practicing what you preach. Hatch Show Print, eat your hearts out. You’ve been out authenticized by a couple of business consultants.

On the thinkabout website it says the following:

“We live in a world of increasingly staged experiences. Interactions with companies are more and more mediated by technology. The rise of postmodernism thought affects personal behavior while the psychology of aging Baby Boomers influences the consumption decisions of us all. And our confidence in our major social institutions had eroded, creating an ever-growing perception of how their practices run afoul of their purposes. Everywhere around us, we detect fakeness.â€

I think I may be detecting just a tiny bit of fakeness right here. They even have a theme song called corporate renegade. I’ll do you a favor and not make you listen to it.

“To be blunt: business offerings must get real. When consumers want what’s real, the management of the customer perception of Authenticity becomes the primary source of competitive advantage – the new business imperative.â€

I don’t mean to be too hard on these guys; perhaps they are on to something valuable. But they keep talking about managing the ‘customer perception of authenticity.’ Real authenticity is not about managing perception; it’s about engaging in the pursuit of real innovation.

“It doesn’t matter what the jargon says, so long as it is spoken in a voice that resonates properly.”-T.W. Adorno, The Jargon of Authenticity (1964)

Authenticity always runs the risk of waxing nostalgic, and the next thing you know you end up with House of Blues (or worse, the Taliban). Martin Heidegger, one of the philosophical cheerleaders of authenticity, spent the last years of his life advocating for a return to a pre-industrial agrarian worldview.

As a final note on this topic, I came across an idea attributed to Jean Baudrillard; the fake is charming, while the simulacrum is not. I have no problem with the honest fake; it’s the pretender, and especially the regressive nostalgic pretender, who offends my sensibility.

As multidisciplinary design teams, our goal should be to claim (or reclaim) authenticity as the purview of innovation. Innovation requires exploring outside of our personal habits and values, without taking ourselves too seriously. As we’ve seen, a little humor helps teams to explore enticing alternatives and engage their audience. Most important is flipping the approach around to explore it from the other’s point of view.

Out of Your Head Innovation

Maybe it’s paradoxical to advocate for the development of fictional models as a means to move toward real innovation. How is it possible that an approach based in the imagination, or more specifically encouraging shared imagination among collaborators, can offer real opportunities for innovation? I believe the value lies precisely in the need to consider the experience of the other, to be forced to get out of our own heads, our own habits, the rituals and beliefs that are so engrained in all of us. The purpose is not to negate or devalue our own experience, but rather to add richness, breadth, and depth to our own experience.

If authentic innovation requires us to get out of our own heads and engage the conversation from a different perspective, story-centered design techniques offer a rapid, iterative, and repeatable process for moving in that direction. To be clear, it is not exclusive or comprehensive in and of itself, but rather an approach that should be used in conjunction with other approaches.

For example, ethnographic and other human-centered research techniques garner real-world insights that are absolutely indispensable to understanding the subtleties and depth of human experience. Prototypes and models allow the iteration of concepts and ideas in increasing fidelity.

What’s in a Story?

In terms of their use in the design process, the definition of a story may vary slightly from traditional concepts, though the core elements remain basically the same; plot, theme, character, and structure. Traditionally stories have a narrative arc, with a beginning, middle and end.

When most people think of story, they think in terms of plot. An important consideration regarding storytelling in the art and design space is that plot often becomes a secondary or even tertiary consideration. It can be hard to figure out the point-to-point precisely because there are so many points of entry and exit, and so many different paths that can be traversed through the story, whatever it turns out to be. In these cases there are other elements intrinsic to the story that become of primary importance, including theme, structure, and character.

One way to think of this is that in the world of designing innovation, the plot is incomplete; it’s always a work in progress. The audience becomes a character in the story and is responsible for the way it works out over time. We need to think more of narrative architecture and less about point-to-point definition. Themes, structures, and characters are put in place and allowed to define some of the details; stories, when used in a forward-looking situation, like prototyping and modeling or even architecture, need to provide a framework where the visitor is engaged and encouraged to tell their own story. And that story becomes the starting point for future modification and revision.

In a sense, this type of design is really metadesign; we’re creating a design where the audience fills in the blanks. We want to create the opportunity for other uses, other stories, and other ideas. Ideas beyond those that we ourselves can imagine.

We live in a world of tremendous interconnectedness between various disciplines. Designers need to be aware of politics and business and cultures. Ultimately, it is a question of value, and values. More than ever, we need to be concerned with value of what we communicate to the individual and to the world in which we live. Design is problem solving, but the problem always comes in a context. As designers we need to work to see that the context is as comprehensive as possible; even when presented with a very specific issue, it is incumbent on us to connect to the larger framework of the world in which we live.

Story provides a structure through which multiple individuals can bring their own experiences and beliefs to bear on a shared experience, enhancing it and growing it over time. And in doing so build communities in ways that don’t oversimplify or reduce our experiences into a homogenized mediocrity. We are looking for excellence, and from all those engaged in the process, including designers, businesses and the public. Now is the age when everyone creates.

What is it that creates that authenticity? What a great subject for story – so much of story is associated with fabrication – but the process of story here – in this blog – and it does a great job of it – is about having an emotional experience as a business owner and having that experience become a meaningful tool to establish credibility. I think we’re, as Americans, self-aware – or in this case self-conscious – we know our pursuit of success has material awards, it’s a meaning vacuum. We have everything on this side of the world – but we reckon with substance and authenticity. We bend over backwards for people in a business context – for people we may avoid in any other context. Strange, huh? That’s the nature of business – or of money. But we do it because we believe our own story about what we offer. Money is a tool to give our best. It keeps us on our best behavior. And brings out our worst simultaneously. Story is the meeting place between the two.

Joseph, thanks for the thoughtful response. I am thinking a lot these days about the intersection of the market and the authentic – and wondering if there is some way to offer the artisinal in a mass-produced situation. I think that there is a new model of storytelling, based on dialog or discourse rather than a one-way ‘controlled’ outbound process.

Would love to obtain a copy of the Pilgrim’s Progress Map you have on your website – do you know where I can get a copy ?